Centenario Canal Irrigation Megaproject will put an end to floods and ecosystems

TEPIC

If stopping the Santiago River’s nutrient flow to the National Wetlands in the early 1990’s caused an ecological disaster, what more harm could come if they took just a little bit more from that ecoregion?

That seems to be the logic of the new and ambitious Centenario Canal construction project being promoted by the federal government and the state of Nayarit for the upper zone of this coastal plain. The project seeks to modernize approximately 106,250 acres and increase the state’s grain production by 50%.

These are development model statistics that appear to go unquestioned, similar to those used by the Echeverría administration in the 1970’s that first opened these delicate ecosystems to investment and large-scale construction projects.

"The Mexican president, Enrique Peña Nieto, announced the construction of the Centenario Canal that will substantially increase the irrigation area of cultivable lands and will increase food production of Nayarit […], benefitting more than 7,000 producers.

“With this, the modernized agricultural lands in Nayarit will grow about 50%, and most importantly: it is expected that the project will increase the state’s production of corn by 500%, rice by 300% and beans by 250%,” states a presidential news release issued Nov. 4, 2013.

"It's an enormous hydro-agriculture infrastructure project: the main canal will be almost 37 miles long and will will carry 60 cubic meters per second of water."

In comparison, the Chapala Guadalajara aqueduct carries a maximum of 7.5 cubic meters, allowing the capital of Jalisco to extract up to 200 million cubic meters annually.

"The distribution network of canals will have a length of about 200 miles," according to the press release. "Five hundred and forty control structures will be built - pumps and conduits – as well as a drainage system and a network of access roads totaling about 270 miles."

"Resources on the order of US$556 million will be invested in the Centenario Canal." In terms of its sustainability, the water supply for this project is guaranteed because it will be fed by the Rio Santiago.

"This project is going to take advantage of the existing infrastructure. Along this river there are already three electric plants: Aguamilpa, El Cajón and La Yesca, with huge water reservoirs," adds the publication.

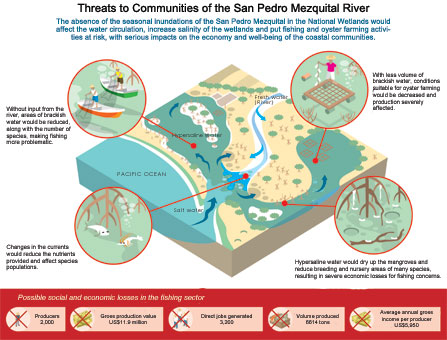

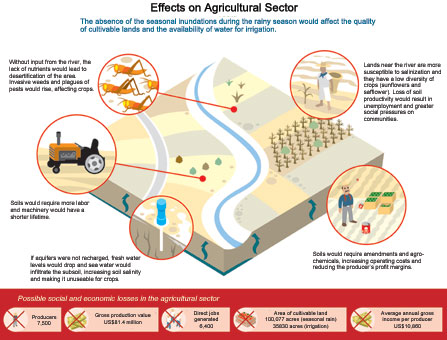

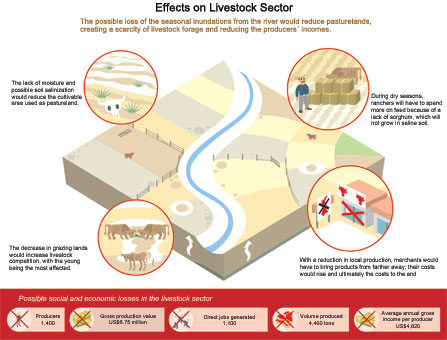

However, it makes no reference to the importance of the floods and the sediments they carry for these ecosystems or to the economic losses that will occur by preventing them. These effects will be seen in fishing, agriculture, livestock farming, and tourism as well as local cultures.

No mention of an environmental impact statement (EIS) is made, and one doesn’t exist that analyzes how the hydrodynamics and fertility of the National Wetlands, a federally designated protected natural area, would be altered.

In the past, the retention of sediments and decreased water volume due to the Aguamilpa Dam has resulted in an impoverishment of downstream soils, the complex but well documented problem of salt intrusion of the aquifers, and the loss of coastal beaches at a rate of 33 feet per year.

The lands that used to benefit from the surplus waters of the Santiago are being transformed little by little into wastelands due to the lack of fertile silt and increasing salinity.

To the south, less water and silt. To the north, the dammed Río San Pedro. All of these areas are found within a Ramsar Site of International Importance that is currently home to the most extensive mangroves on the Mexican Pacific.